In the hushed halls of the National Gallery, a visitor stands not before a canvas, but before a high-resolution screen. A magnified detail of a Song Dynasty landscape scroll glides silently under their fingertips, revealing brushstrokes and paper textures invisible to the naked eye. This quiet moment encapsulates a profound cultural shift: the migration of paper-based art from its traditional, tangible realm into the luminous, fluid domain of the digital. The journey from paper to screen is not merely a change of medium; it is a complex negotiation of materiality, authenticity, and cultural symbolism that is redefining our relationship with art itself.

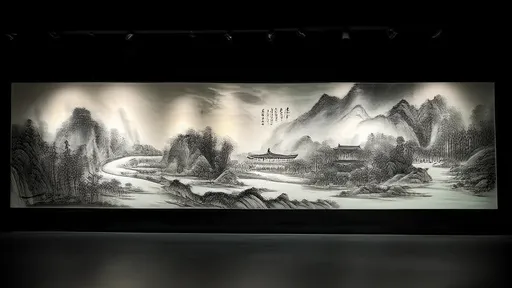

The very essence of paper art has long been rooted in its materiality. For centuries, paper was not just a passive support but an active participant in the artistic dialogue. The absorbent, fibrous surface of Xuan paper, for instance, was integral to the practice of Chinese ink wash painting. The way the ink bled and settled into the paper's texture was a calculated element of the artwork, a collaboration between the artist's intention and the material's inherent character. The weight, the feel, the faint scent of aged paper, and even the audible crinkle as a scroll is unrolled—these are sensory experiences that constitute the artwork's aura, its unique presence in time and space. This physicality is inseparable from the cultural rituals surrounding such art. The careful unrolling of a handscroll, a private, sequential viewing that unfolds in time, is a performative act that binds the viewer to the object in a deeply personal way.

As these works are digitized, this material presence undergoes a fundamental transformation. The physical object is translated into a stream of binary code—a dematerialization that liberates the image from its fragile, earthbound vessel. Suddenly, a millennia-old manuscript can be accessed from a smartphone in another hemisphere. The digital surrogate offers unprecedented access, allowing for close-up inspection without the risk of damage from light, humidity, or human touch. Conservationists can use multispectral imaging to uncover erased texts or preliminary sketches hidden for centuries. This is the great promise of the digital age: the democratization and preservation of cultural heritage on a global scale. Art that was once locked away in climate-controlled vaults, accessible only to a privileged few, can now be studied and admired by millions.

Yet, this liberation comes at a cost. The digital image, for all its clarity and accessibility, is ontologically different from the physical artifact. It lacks the singular "hereness" and "nowness" that defines the original. A digital file can be perfectly replicated an infinite number of times; there is no original copy in the digital realm, only identical data sets. This erodes the concept of authenticity that has been a cornerstone of art history and the art market. When every JPEG is as "real" as the next, what happens to the aura of the unique object? The cultural weight carried by a sheet of paper that was handmade, inscribed upon, and passed down through generations cannot be encoded into pixels. The digital version is a ghost of the original—a magnificent, useful, and enlightening ghost, but a ghost nonetheless.

Furthermore, the interface of the screen imposes its own aesthetic and experiential framework. The cool, backlit glow of an LCD screen is a world away from the way natural light plays off the textured surface of paper. The act of pinching and zooming on a touchscreen is a utilitarian gesture, devoid of the reverence and ceremony of handling a physical scroll or codex. The digital platform re-contextualizes the artwork, often placing it alongside advertisements, social media feeds, and other digital content, which can trivialize its cultural significance. The artwork becomes one more piece of content in an endless stream of information, competing for our attention in an economy of clicks and scrolls. This new context can flatten the hierarchical value we traditionally assign to great works of art.

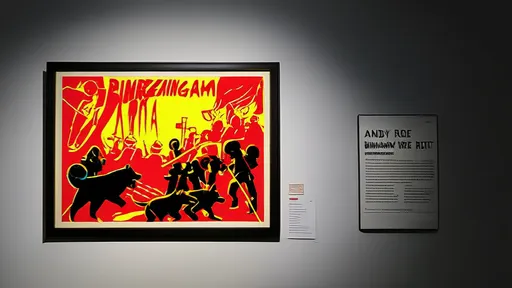

However, to view this transition as a simple loss is to ignore the new forms of meaning and engagement that are emerging. Digital technology is not merely a tool for replication; it is a new medium for creation and interpretation. Artists are now creating works that are "digital-native," exploring concepts of materiality that are unique to the computational environment. These works might simulate paper texture algorithmically or use code to generate infinite, non-repeating variations on a theme, something impossible in the physical world. The cultural symbolism is shifting from the value of the rare object to the value of access, data, and network connectivity. In this new paradigm, an artwork's importance is measured not only by its physical provenance but also by its searchability, shareability, and the richness of the metadata attached to it.

The most profound impact may be on the narrative itself. A physical book or scroll presents a fixed, linear narrative. Its sequence is bound by its material form. A digital archive, by contrast, is inherently non-linear and modular. A user can jump from the first page of a medieval manuscript to the last, then to a related scholarly article, then to a map of the region where it was created. This hypertextual experience shatters the traditional, authoritative narrative and empowers the viewer to construct their own unique pathways through cultural history. The story of the artwork is no longer told solely by the curator or the art historian; it is co-authored by the user's curiosity and the algorithmic logic of the database.

Ultimately, the relationship between the paper original and its digital echo is not one of replacement, but of palimpsest. The digital layer does not erase the physical; it writes over it, creating a complex, multifaceted entity. The screen becomes a window back to the paper, and the paper, in turn, is re-contextualized by its digital afterlife. The future of paper art in the digital age lies in this dialectical tension. It challenges us to develop a new literacy—one that appreciates the profound materiality of the original while embracing the transformative potential of its digital manifestation. We are learning to value both the silent, enduring presence of the paper in the museum case and the dynamic, accessible image on the screen, understanding that together, they form a more complete, though more complicated, picture of our cultural memory.

As we navigate this transition, we are forced to ask fundamental questions: What is the true essence of an artwork? Is it the physical material, the visual image, the cultural idea, or the sum of its interactions with an audience across time? The journey from paper to screen has no single destination, but the voyage itself is reshaping our answers. In the space between the fiber and the pixel, a new chapter in the history of art is being written, one that acknowledges the past without being bound by its limitations, and that looks to a future where culture is both preserved in amber and set free in the light of the screen.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025