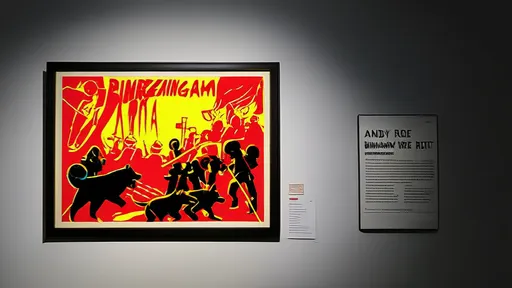

In the hushed halls of Sotheby's New York, a piece of American history hangs suspended between its troubled past and its commodified present. Andy Warhol's 1964 Birmingham Race Riot, a silkscreen print that captures one of the Civil Rights Movement's most harrowing chapters, is poised to transition from a private collection to the public spectacle of the auction block. This journey from personal artifact to high-stakes lot is more than a simple transaction; it is a narrative about memory, value, and the complex afterlife of images in a culture obsessed with both remembering and monetizing its traumas.

The artwork itself is a stark departure from Warhol's celebrated depictions of consumer goods and celebrity icons. Instead of Campbell's soup cans or Marilyn Monroe's smiling face, the print reproduces a photograph by Charles Moore, originally published in Life Magazine. The image is a chaotic tableau of the brutal police response to a peaceful protest in Birmingham, Alabama. In it, we see police officers with snarling dogs attacking Black demonstrators, the tension and violence frozen in the high-contrast black and white of Warhol's silkscreen process. He did not create the image, but he appropriated it, lifting it from the pages of mass media and transforming it into a work of art. This act of appropriation is central to the piece's power and its perpetual ambiguity.

For decades, this particular print resided in the hands of a private European collector, a ghost in the sprawling archive of Warhol's work. Its existence was known to scholars and art historians, but it was largely shielded from the public eye. In this private sanctuary, the work functioned as a secret, a piece of American racial violence held at a geographical and cultural remove. Its value was intrinsic, tied to the owner's personal connection to the piece and its historical significance, rather than a price tag determined by the volatile art market. This long period of seclusion adds a layer of mystique to its impending sale, framing it as an emergence, a rediscovery of a potent cultural relic.

The decision to bring the Birmingham Race Riot to auction signals a critical shift. The private collection is a closed system, a world of personal taste and discretion. The public auction, by contrast, is a theater of capitalism. It is a space where cultural value is explicitly and performatively translated into monetary worth. The gavel's fall will not merely signify a change of ownership; it will assign a new, public number to this difficult piece of history. This transition forces a confrontation between the artwork's solemn subject matter and the glittering, often superficial, world of high-stakes art collecting. Can the gravity of the Civil Rights struggle be adequately housed within this commercial framework? The auction house, of course, positions the sale as a celebration of Warhol's genius and the work's historical importance, but the subtext is a profound tension between remembrance and commodification.

Warhol's entire artistic project was preoccupied with the relationship between repetition, media, and desensitization. By reproducing the photograph of the Birmingham riot, he was asking uncomfortable questions about how society consumes images of suffering. When a photograph of violence becomes a print, and that print becomes an edition, and that edition becomes a collectible asset, what happens to the emotional and ethical weight of the original event? The market journey of this piece is the ultimate extension of Warhol's inquiry. The auction process itself—the cataloging, the pre-sale exhibitions, the bidding paddles rising in a crowded room—is a form of spectacle that mirrors the media spectacle from which the image was born. We are forced to watch ourselves watching history being sold.

Provenance, the history of an artwork's ownership, is a key driver of value in the art market. For a work like the Birmingham Race Riot, its provenance is uniquely charged. Its journey from Warhol's Factory to a private European collection and now to the global stage of a Sotheby's auction is a story that will be meticulously documented and marketed. This narrative becomes part of the artwork's aura, enhancing its allure and, consequently, its estimated price. The buyer, whether an institution like a museum or another private individual, will not just be purchasing a Warhol; they will be purchasing a chapter of this narrative, becoming the next custodian of an object that bridges art, journalism, and social history.

The sale also raises pressing questions about the role of cultural institutions. There is an implicit hope, or perhaps a public demand, that such a historically significant work should find a home in a museum. A museum would ostensibly de-commodify the piece, placing it in a context of education and public access rather than private enjoyment. It would allow the work to fulfill its potential as a tool for confronting a painful national past. However, the astronomical sums involved in acquiring a major Warhol often place such works beyond the reach of all but the most heavily endowed public institutions. The likely scenario is a fierce bidding war between ultra-wealthy private collectors, ensuring the work disappears behind closed doors once again, its market journey pausing before inevitably restarting in another decade or two.

Ultimately, the market journey of Andy Warhol's Birmingham Race Riot from private collection to public auction is a microcosm of a larger cultural dynamic. It highlights the uneasy but inextricable link between historical trauma and contemporary capital. The artwork, born from a moment of profound social upheaval, now exists as a luxury asset. Its power to shock, to sadden, and to provoke thought remains, but that power is now filtered through the prism of multi-million-dollar valuations and the rarefied air of the auction world. As the gavel prepares to fall, it does so on more than just a piece of art; it falls on the ongoing American struggle to reconcile its history with its marketplace, a struggle as relevant today as it was in 1964.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025