In the heart of The Hague, where Vermeer's light once danced across canvas, a new artistic dialogue is unfolding—one that bridges centuries and continents through the humble yet profound medium of paper. Paper Language Through Millennia: Cross-Cultural Dialogue of Contemporary Chinese Paper Art in The Hague represents more than an exhibition; it is a conversation between civilizations, where ancient Chinese paper-making traditions meet contemporary artistic practices in a European cultural capital.

The timing of this exhibition coincides with the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and the Netherlands, though curator Dr. Lin Wei insists this is merely a fortunate coincidence. "We began planning this three years ago," she explains, her fingers gently tracing the edge of a hanging paper installation that seems to float between two gallery walls. "The real impetus came from noticing how contemporary Chinese artists were rediscovering paper not just as a surface, but as a substance with its own language, its own history."

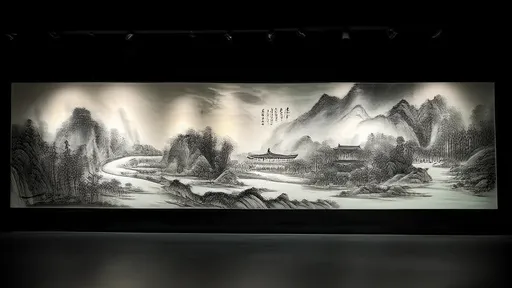

Walking through the exhibition spaces, one encounters works that challenge conventional understanding of paper art. Zhang Min's “Breathing Mountains” consists of layered rice paper that appears to undulate with the gallery's air currents, creating the illusion of distant peaks shrouded in mist. The piece required two tons of specially treated Xuan paper and incorporates microscopic LED lights between layers that pulse gently, mimicking the rhythm of traditional Chinese landscape painting while introducing technological elements that would have been unimaginable to ancient masters.

What makes this exhibition particularly significant is its location in The Hague—a city known more for international law than cutting-edge contemporary art. Museum director Johannes van der Berg acknowledges this with a thoughtful expression. "We deliberately chose The Hague rather than Amsterdam or Rotterdam precisely because it lacks an established Asian contemporary art scene. We wanted these works to speak for themselves without the burden of preconceived notions or established critical frameworks."

The exhibition features thirty-five artists, ranging from established figures like Qiu Zhijie to emerging talents such as Wang Luyan, whose delicate paper sculptures explore themes of fragility and resilience. His piece “The Unbroken Line” consists of a single continuous strip of handmade paper that forms an intricate lattice structure spanning an entire room, somehow managing to appear both impossibly delicate and remarkably strong.

Historical context forms an important subtext throughout the exhibition. Wall texts thoughtfully explain how paper arrived in Europe via the Silk Road, fundamentally transforming Western civilization through the dissemination of knowledge. Yet as Professor Elena Rossi, an art historian specializing in cross-cultural exchange, notes in the exhibition catalog: "We rarely consider what happened to paper arts in China after this transfer. While Europe developed printing presses, Chinese artists continued to explore paper's artistic potential in ways that remained largely unknown outside Asia until recently."

Several works directly engage with this historical narrative. Xu Bing's “Square Word Calligraphy” installation invites visitors to write their names using his hybrid writing system that merges Chinese character structures with English letters—all on traditional paper scrolls. The interactive piece has proven particularly popular with Dutch school groups, who queue patiently for the opportunity to create their own cross-cultural artifacts.

The exhibition design itself merits attention. Rather than grouping works by artist or chronology, curator Lin has organized them thematically, creating dialogues between pieces that might otherwise never speak to each other. In one striking juxtaposition, a minimalist installation of torn paper fragments by Liang Shaoji sits beside Chen Chuncheng's vibrant, digitally-inspired paper collages. The contrast highlights the incredible diversity of contemporary Chinese paper art while suggesting underlying connections in materiality and process.

Technical innovation features prominently throughout the exhibition. Many artists have developed proprietary paper treatments to achieve specific effects. Li Hongbo's astonishing paper sculptures that stretch and contract like accordions required developing a special honeycomb structure and adhesive formula that took three years to perfect. Meanwhile, Peng Wei creates her delicate paintings on the pages of antique books using techniques derived from traditional Chinese painting but applied in entirely new contexts.

The response from European critics has been notably thoughtful. While some have questioned whether grouping these artists primarily by their material constitutes a meaningful curatorial approach, most have praised the exhibition for challenging Western perceptions of Chinese contemporary art. As one Dutch reviewer wrote: "We've grown accustomed to political pop and cynical realism from China. This exhibition reveals an entirely different artistic landscape—one less concerned with explicit commentary and more engaged with materiality, tradition, and quiet contemplation."

Educational programs accompanying the exhibition have proven unexpectedly popular. Workshops on Chinese paper-making techniques, calligraphy, and contemporary paper art practices regularly sell out weeks in advance. "There's genuine curiosity about these techniques," notes education coordinator Marijke van der Waal. "Many participants express surprise at paper's versatility—how it can be sculpted, layered, torn, embedded with other materials, or made to appear completely different from what we normally think of as paper."

Perhaps the exhibition's most significant achievement lies in its demonstration of how traditional materials can facilitate contemporary cross-cultural understanding. As artist Gu Wenda observes during a gallery talk: "Paper contains memory. It remembers the tree it came from, the water it was soaked in, the hands that pressed it. When we work with paper, we're not just making art—we're continuing a conversation that began two thousand years ago." His own contribution to the exhibition, a massive installation made from human hair pulp paper, embodies this philosophy through its transformation of a personal material into a medium for universal expression.

The exhibition's impact extends beyond the gallery walls through an ambitious publication that includes not only high-quality reproductions but also essays by scholars from China, Europe, and North America. This academic component ensures the conversations started here will continue long after the exhibition closes.

As the cultural director of The Hague, Pieter van der Horst, reflects: "In a world increasingly dominated by digital experiences, there's something profoundly human about returning to such an ancient physical medium. This exhibition reminds us that some conversations are best had not through screens, but through materials that carry the weight of history and the touch of human hands."

Paper Language Through Millennia continues through the end of the season, with several works already acquired for the museum's permanent collection—ensuring that this cross-cultural dialogue will remain part of The Hague's artistic conversation for years to come. The exhibition successfully demonstrates that in the right hands, paper can indeed speak across millennia, carrying messages between cultures and through time with a clarity that often eludes more modern forms of communication.

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025

By /Oct 24, 2025